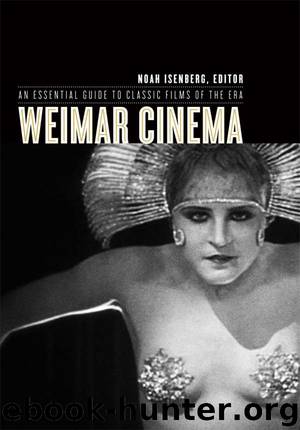

Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era (Film and Culture Series) by Noah Isenberg

Author:Noah Isenberg [Isenberg, Noah]

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: Criticism, Performing Arts/Film &, Video/History &

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2008-12-31T05:00:00+00:00

[

NINE ]

* * *

METROPOLIS (1927)

CITY, CINEMA, MODERNITY

* * *

ANTON KAES

One of the crucial antinomies of art today is that it wants to be and must be squarely utopian, as social reality increasingly impedes utopia, while at the same time it should not be utopian so as not to be found guilty of administering comfort and illusion. If the utopia of art were actualized, art would come to an end.

THEODOR W. ADORNO, Aesthetic Theory

OPENING NIGHT

On January 10, 1927, all of Berlin’s forty newspapers were abuzz with anticipation and excitement. Metropolis, the monumental new film by Fritz Lang, one and a half years in the making, was finally to open after an unprecedented advertising campaign that had run for several months. It was widely known that Metropolis was the most expensive and ambitious European film production to date, with an unheard-of cost of 5.3 million Reichsmark (almost four times its budget); that its shooting ratio was 1:300 (with more than 1 million meters of film exposed); and that it employed thirty-six thousand extras, including seventy-five hundred children and one thousand unemployed individuals whose heads had been shaved by one hundred hairdressers for a scene that in the final cut lasted less than a minute. Statistical hyperbole and such slogans as “a film of titanic dimensions,” an “Über-film,” and “the greatest film ever made, one of the most eternal artworks of all times,” promised an epic film that could compete with such American spectacles as Raoul Walsh’s three-hour extravaganza, The Thief of Baghdad (1924) or Fred Niblo’s Ben Hur (1925), which had been shown in Berlin just a year earlier. Metropolis was also eagerly awaited as a sequel to Lang’s successful megaproduction of 1924, the two-part Die Nibelungen (The Nibelungs), which had established him as the most daring filmmaker of the 1920s both in visual style and ideological ambition. Dedicated to the “German Volk,” Die Nibelungen translated the archetypal German epos into stunning images of gigantic medieval castles and prehistoric forests, built in concrete for Ufa’s Neu-Babelsberg studios near Berlin (Hake 1990). Lang, who had studied architecture and painting before he turned to filmmaking, infused all of his films with a rich spatial imagination; he molded his characters and their fictional world to fit his design. Not surprisingly, it was the big-city architecture of New York that struck him first when he visited the United States in the fall of 1924:

Download

Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era (Film and Culture Series) by Noah Isenberg.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32019)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16029)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14076)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13365)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13241)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9343)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9292)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7313)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6622)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)